- Peloton invented a new category, has a beloved product with off-the-charts NPS scores, a rabid member base, and a largely fixed cost structure that will scale beautifully over time.

- Peloton was already seeing massive revenue growth even before COVID-19, but is now seeing overwhelming demand. With no need to advertise, CAC is plummeting.

- Cheaper versions of the bike and treadmill will accelerate growth even faster in the future. Leveraging the fixed cost content production across millions of future subs should be highly profitable.

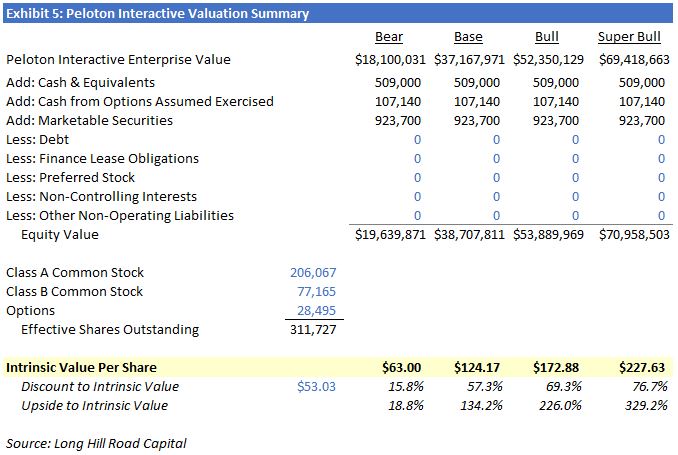

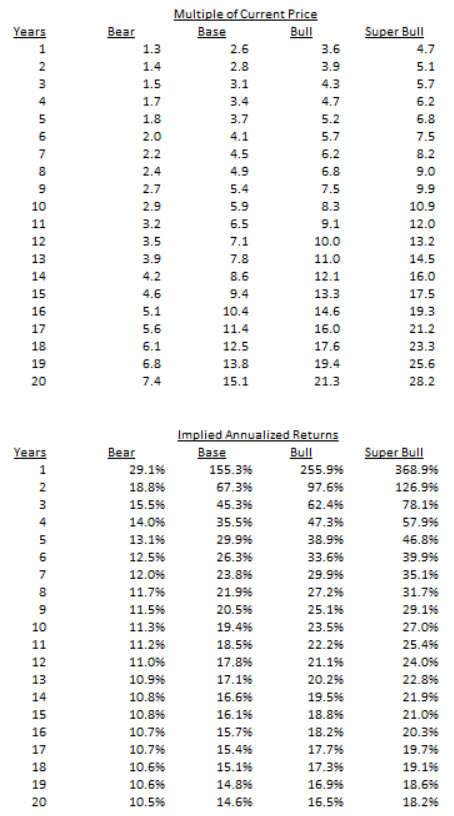

- My Base case suggests PTON is worth well over $100 per share today (versus its $53.03 current price today), and could appreciate by 15x over the next 20 years.

Peloton Interactive (“Peloton”) is a rapidly-growing interactive fitness company that created its category from scratch, and has a beloved product and service, a rabidly enthusiastic fan base, and a massive long-term market opportunity. In addition, Peloton has a highly profitable future due to the tremendous fixed cost leverage it benefits from as a result of producing content that it can broadcast to an infinite number of potential subscribers.

It could be said that Peloton’s business is Netflix’s business with three big differences: 1) a smaller addressable market in terms of subscribers, 2) dramatically less content production required and the content production itself is dramatically less expensive, and 3) subscribers have to pay up front for the equipment to necessary to become a subscriber. On the last point, imagine we had to buy a $750 device from Netflix in order to become a $13 per month subscriber—that’s roughly the same math as Peloton’s up front cost for the bike relative to the ongoing subscription cost.

Prior to COVID-19, Peloton already had an incredibly attractive product, service, and value proposition, but the pandemic has brought Peloton’s future forward by several years. Demand for Peloton’s bikes and treads is through the roof, which has some profound knock-on effects. For example, that massive demand has temporarily outstripped the company’s supply of bikes (tread sales are paused due to the in-home assembly requirement), which has allowed the company to eliminate all advertising spend (excluding the nascent Germany market where it is still building a brand). That means Peloton’s customer acquisition costs are plummeting. And the larger the subscriber base gets, the more the company benefits from free word-of-mouth marketing. The result is Peloton should have dramatically lower selling and marketing requirements going forward and over the long term.

Peloton

For those who don’t know, Peloton sells high-end stationary bikes and treadmills that have an integrated tablet screen. The company has fitness studios primarily in New York and London where it streams its content in front of a live audience of indoor cyclists and treadmill runners. Subscribers at home can partake in these classes live, in which case the instructors may call out your name (if it’s your 100th ride, for example), or on-demand at a later time.

The bikes and treadmills (“Connected Fitness products”) are integrated with the system so that, with the bike, users can see their speed (“cadence”), level of difficulty (“resistance”), and total output measured in kilojoules. I don’t own the Tread yet, but the equivalent metrics are speed, incline, and total output.

There is a wide variety of class content in terms of instructor personalities, the type of ride, and the length of the ride. High energy music is blasting. You can see the leaderboard on the right side of your screen that includes your position among all the people who are taking, or who have ever taken, that class. You can filter it by a number of variables to get a more focused competitive set (age, gender, hashtag, only people you follow, etc.). You also see your PR (personal record for output) in the leaderboard ahead of you, which acts as a motivating factor.

The system stores all your historical workouts and reams of data, so you can easily track your progress. You can pair a heart rate monitor so that data shows up on the screen and is stored historically. If you’re at all competitive and/or data driven, it’s addicting to see your progress.

PSA: Use my referral code 39VER7 if you buy one. Doing so will give you (and me) a free $100 credit towards Peloton store accessories. You need to have the accessories in your cart to be shown the option to enter a referral code.

Market Opportunity

Peloton invented this connected fitness concept, so there isn’t an existing market size to look to like there is with more established markets. But we can look to related markets to get some sense. For example, there are 183 million gym memberships globally, including about 90 million in the markets where Peloton is already operating (U.S., Canada, U.K., and Germany). The number of gym memberships isn’t a perfect proxy since determining how many of those people would consider buying a Peloton bike, tread, or rower in the future is really a wild guess.

Today, Peloton has just over 1 million Connected Fitness subscribers, 177,000 digital subscribers, and another 1.1 million or so on an extended free digital trial. So if you think the number of gym members is the right market size, Peloton has a tiny fraction of the market.

But certainly, not all of them are going to buy a Peloton product.

Alternatively, you can look at the number of treadmills that are in homes in the U.S. right now. According to management, there are about 34-35 million treadmills in U.S. homes. Given an average useful life of about 7 years, about 5 million of those are scraped every year and another 5 million are purchased (not necessarily by the same people).

Right now, the big difference between these treadmills and the Peloton tread is price. The Peloton Tread costs $4,295 for the “Basic” package without accessories. That’s expensive for most people. However, most Peloton buyers finance their purchases, and the company offers the Tread for $111 per month for 39 months with 0% interest. That’s more affordable for more people.

But what’s really interesting is Peloton’s strategy is to become affordable for everyone. On the company’s fiscal second quarter conference call, management said:

Over time, our #1 goal is to make the Peloton experience more accessible to more people across all demographics. As we have discussed before, our long-term goal is to have a better/best product portfolio. With high-volume, scale production, marketing efficiencies and strong subscriber unit economics, we see an opportunity to pass savings on to the consumer, allowing us to broaden our reach and increase our addressable market.

If or when Peloton comes out with a “mass market” version of the Tread, I think it’s going to suck the air out of the at-home treadmill industry. I would bet that most at-home treadmills are effectively clothes hangers. Someone bought one for a New Year’s resolution, tried it for a bit, and then lost interest.

The big difference with Peloton is engagement. People use it because it’s fun, engaging, competitive, and social. The average number of monthly workouts per Connected Fitness subscriber reached an all-time high last quarter of 17.7; that’s up from 7.5 in 2017. Part of that is probably a greater mix of shorter “floor” workouts like yoga, meditation, boot camp, strength training, etc. but some of it appears to be bike/tread workouts too. Management has said more recent cohorts are working out even more than older cohorts, who are still working out a lot.

So over time, I’d expect the Peloton to capture a decent share of those 35 million treadmills in U.S. homes between the existing Tread and mass market version, which I expect to be released either late this year or next year. Put that in context though—there are just over 1 million Connected Fitness subscribers right now. Getting 10 or 15 million or more from just treadmills sales just in the U.S. over the next several years would be massive growth. Throw on more bikes, a cheaper version of the bike, and a better/best version of the rower, and we’re talking about very big numbers relative to the current ~1 million Connected Fitness subscribers.

What I find super interesting though is the fact that Peloton is expanding the market. Peloton’s S-1 filing states:

According to our 2019 Member Survey, four out of five Members were not in the market for home fitness equipment prior to purchasing a Peloton Connected Fitness Product.

I can tell you I was not in the market for a stationary bike before I bought the Peloton bike. You couldn’t pay me to ride a stationary bike. I’d be bored out of my mind. But adding a tablet and the engaging content, data tracking, social and competitive element completely changes the game. One of my good friends was very skeptical about the bike when I pitched him on it, saying the same things about being bored. He bought one and now loves it too.

So the 35 million treadmills in the U.S. would seem to understate Peloton’s potential U.S. treadmill TAM. I am going to buy a Tread once they resume delivering them, but I’ve never owned a treadmill before. How big could the real market potential be? I don’t know with any certainty, but it seems significant.

Management has said the mass market treadmill is probably going to cost about the same as the bike does today. That’s about $2,245, and you can buy the bike for $58 per month over 39 months at 0% interest. That’s pretty affordable, and an absolute steal if you’re actually going to use it and improve your health.

So I’m pretty bullish on the number of Connected Fitness subscribers the company will have globally over the long term. The founder and CEO John Foley made this comment at the UBS conference in December:

Our True North is going from close to 600,000 subs today to 20 million subs, pick a number, in 10 years…. and we feel like we can do that on the strength of our current R&D portfolio, our current public portfolio, and the things that are in R&D, and a few more markets.

He obviously wasn’t giving guidance, but I don’t think 20 million CF subs in 10 years is unreasonable.

Rabid Member Base

Until you own a Peloton yourself, you won’t appreciate it for what it is. It may seem like another fitness fad in an industry that’s notorious for fitness fads. So many people buy fitness products and never use them, so I think that explains much of the natural skepticism towards Peloton that exists in the investment community.

I’d encourage you to join the Peloton Facebook group and just read the posts every day for a while: https://www.facebook.com/groups/pelotonmembers

Every day, I read these deeply personal stories about how someone had some personal tragedy, found Peloton, and it helped them recover mentally and/or physically. Or someone who has lost 60 pounds posting before and after photos. It’s almost shocking how willing so many of these people are to share private, personal life stories with complete strangers. But they get great feedback with Likes and encouraging comments. I haven’t seen this sort of thing in an online community of strangers before. The members are truly evangelists for Peloton.

One metric that I love looking at is Net Promoter Scores (NPS). The NPS question is basically, “On a scale of 1-10, how likely are you to recommend this product or service to a friend?”

Any positive NPS score over 0 means there are more promoters than detractors. Anything over 0 is considered “good,” over 50 is considered “excellent,” and over 70 is considered “world-class.”

According to management, the NPS for the bike experience has ranged from 80 to 93 since they’ve been measuring it. I’m not sure I’ve seen an NPS that high for anything. For the tread, they have said it is “approaching 80,” so presumably high 70s.

I believe those numbers because I know the experience, and I’ve been reading the messages in the Facebook group for about three years. By the way, the Facebook group has over 304,000 members, so it’s equivalent to about 30% or so of the last reported number of Connected Fitness subscribers. The number of members is constantly increasing too—I track that data over time.

Economic Model

Peloton’s has two primary revenue lines—Connected Fitness Products, which are the physical sales of the Peloton bikes and treads, accessories, and related products, and Subscription.

Customers buy the bike or tread up front (the majority finance it at a 0% APR for relatively low monthly payments) and then subscribe to the live and on-demand content for an ongoing $39 per month.

Connected Fitness Products seem to have a gross margin in the 40%-45% range, depending on the mix of bikes versus treads. Bikes have higher margins primarily because the company makes so many of them and gains efficiencies with volume. The bike may be 45%-50% gross margin and the tread may be 35%-40% right now until it scales or something close to that.

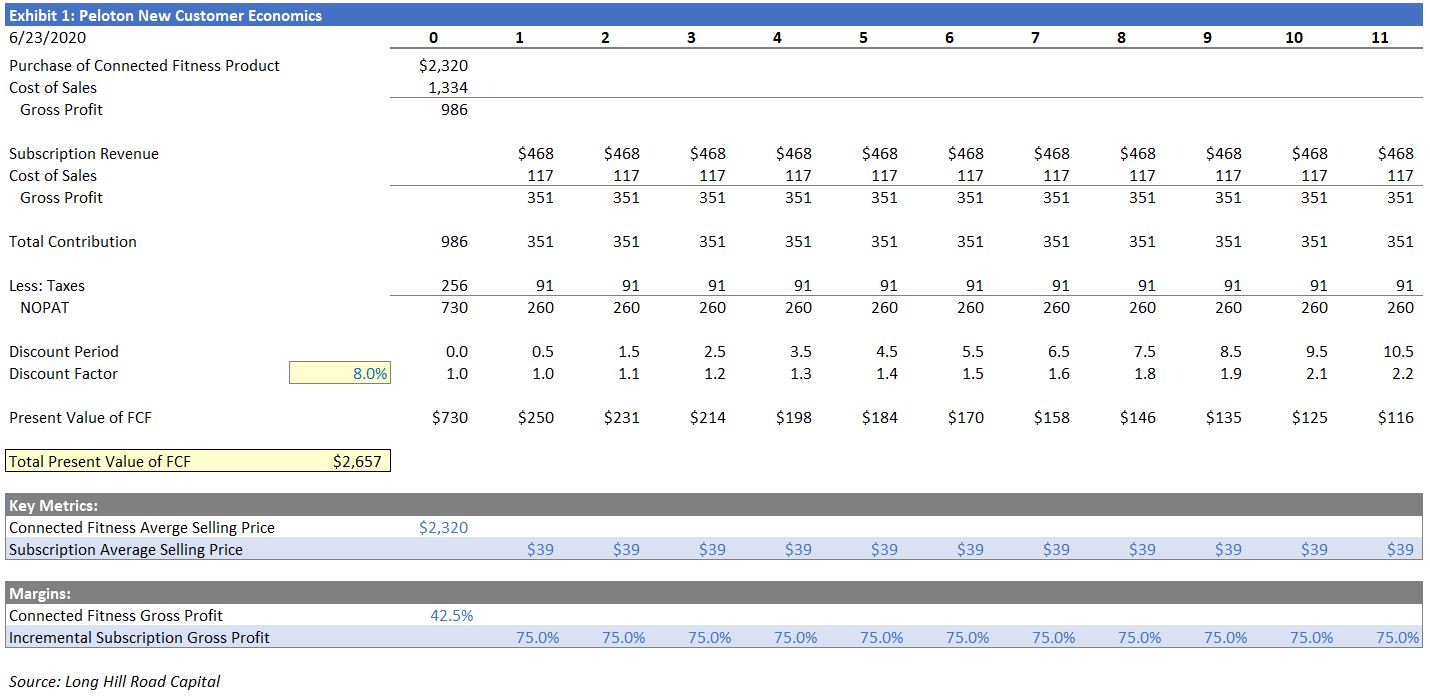

Here is an exhibit I made showing the new customer economics. As you can see, customers buy the Connected Fitness Product up front, on which Peleton might make a 42.5% gross margin on average. Then the customer pays $39 per month for an average customer lifetime of about 11 years, on which Peloton probably makes a 75% incremental gross margin on. So as you can see, the present value of that revenue, at an 8% discount rate, is about $2,657 per new Connected Fitness subscriber.

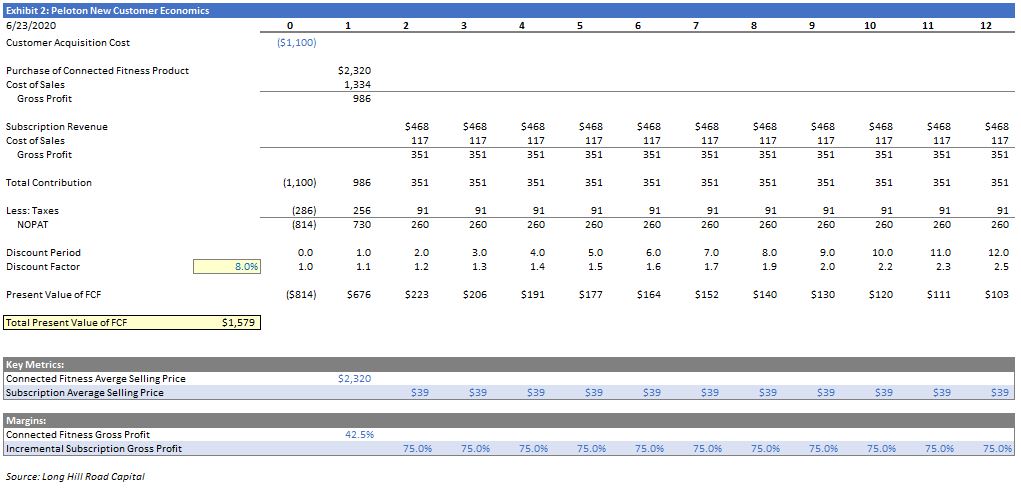

I can further add in the customer acquisition costs up front, assume that marketing drives the purchase exactly one year later, and then the same relationship begins.

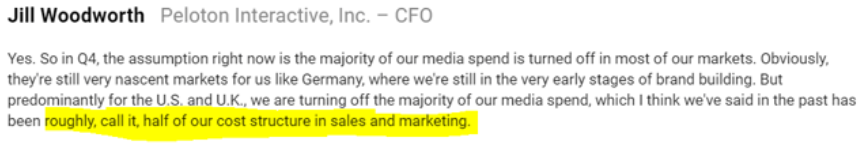

The actual customer acquisition cost was $1,005 in fiscal 2018 and was $1,105 in fiscal 2019. But that’s in free fall now that COVID-19 is driving so much organic demand. Not only is demand through the roof, but the company has a big backlog of orders they need to fulfill, so it doesn’t make sense to spend money on advertising right now. So management is eliminating all media spending in its fiscal fourth quarter ending June 30 (with the exception of in the nascent German market for brand building purposes). The CFO said that should work out to about half of sales and marketing spending going away in the fourth quarter.

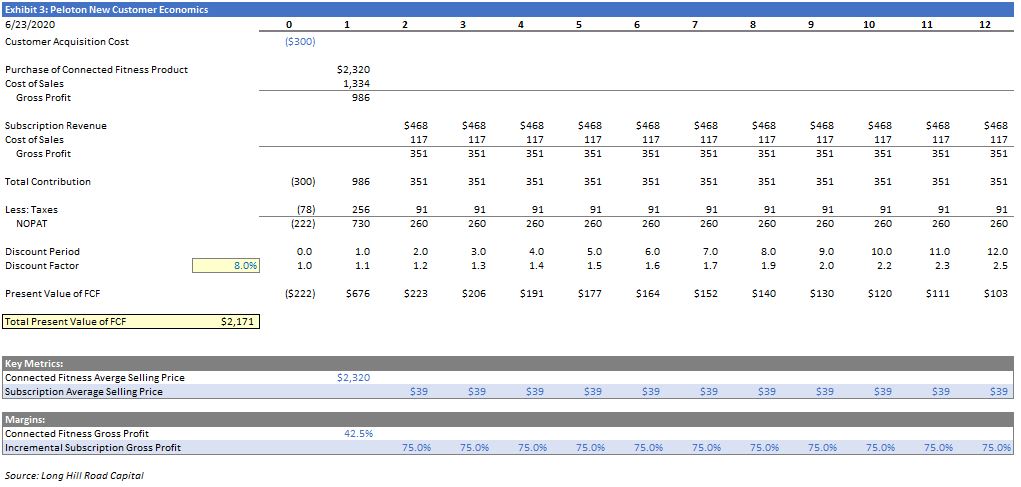

If we get 1 million gross adds next fiscal year (7/1/2020 – 6/30/2021) and the company spends, let’s say, $300 million on sales and marketing, then customer acquisition cost would be $300, down from over $1,000. Let’s plug that into the new customer economics exhibit.

As you can see, the present value of every new Connected Fitness subscriber goes from $1,579 to $2,171. So it’s a pretty attractive customer relationship, and COVID-19 has made it even more attractive. Even pre-COVID, the payback period on CAC was almost immediate due to the gross profit on the product sale. Post-COVID, that up front gross profit is probably going to be something like 3x the new lower CAC.

Strategy

According to the company’s S-1 filing, the company’s aided brand awareness in the U.S. was 67% as of April 3, 2019. Management has repeatedly said that purchase intent follow brand awareness.

The two biggest concerns that potential customers have when considering buying a Peloton bike or tread are 1) price, and 2) “will I use it?”

Price

On price, management has two primary strategies. First, the bike costs $2,245 plus the cost of any accessories, but it offers 0% financing through its financing partner, Affirm. That makes the bike cost as little as $58 per month for 39 payments. Similarly, the Tread costs a hefty $4,295 but $111 per month for 39 months with the 0% financing.

I haven’t independently verified this, but management claims the average gym membership costs $58 per month. There are the $10 per month Planet Fitness memberships and the expensive Equinoxs of the world, so that seems reasonable. For a couple, the gym might average $116 per month. Financing the bike at $58 for 39 months plus the $39 per month subscription fee means it would cost $97 per month for 39 months before dropping to $39 per month forever. That’s not a bad alternative, especially if you have more than one household member using it, which costs nothing extra. You can have up to 5 household user accounts.

Even still, that’s not a “mass market” price. That’s why management’s strategy is to have a “better/best” strategy—one high end model and one mass market model. There had been rumors that the mass market Tread was going to be released this year, but COVID-19 has extended that out further. With all their showrooms closed, and their technicians not able to enter homes yet, they don’t feel it’s an ideal time to launch new products, which tend to have more people buying in showrooms after testing them out than online sight-unseen. If that’s the real reason, I’m not 100% certain I believe that. Rolling out a mass market Tread right now would probably sell like hot cakes.

Personally, I believe the real reason is two-fold. First, they have such a huge backlog in bike orders right now they simply don’t have the manufacturing capacity yet to roll out any new products. Order-to-delivery times, which are usually about a week, are now 6-8 weeks or 7-9 weeks when I check in my area, depending on the day. It had been 10-12 weeks at one point. Second, their bike volumes have reached meaningful manufacturing scale, which means they make great gross margins on the bike. They don’t explicitly disclose bike gross margins, but looking at their financials, it seems like they might make 45%-50% on the bike sales. So since they have limited manufacturing capacity relative to demand right now, doesn’t it make sense to focus all of it on the bike, which are far more profitable? I think so.

In any case, last year Peloton acquired one of its two manufacturing partners, Tonic, which is based in Taiwan. Since then, they’ve been investing in a new state-of-the-art facility that’s going to meaningfully increase capacity. This facility is scheduled to come online and be ready for “holiday demand” this year.

Back to my original point of the better/best strategy—I think the mass market Tread will be at the bike’s current price point—$2,250 or so. Management said that at the Goldman conference in February of this year. I’m super bullish on the consumer interest in that product. 5 million people in the U.S. buy a treadmill every year, and that seems to be within the usual price range of a good quality treadmill. I could see 1 or 2 million sales per year in the U.S. alone once that gets going.

I think the mass market bike could cost something around $1,500 or $1,600. That would be monthly payments of about $40 instead of $58. That would further lower any reluctance their might be to buying one. On one hand, it’s natural to wonder how much cannibalization there will be as consumers flock to the cheaper versions. They do expect to make lower gross margins on the cheaper versions.

But I’m not worried about that at all. The key to the strategy is growing the subscriber base. Making a bit lower margins on product sales in the future, which they have said to expect, is well worth the benefits of scale in product manufacturing, word-of-mouth marketing, and the subscription economics. I believe one more subscriber probably has 75%+ incremental subscription gross margins. More on that later.

Will I use it?

“Will I use it” is the other consumer concern. At home fitness products are notorious for becoming clothes hangers or dust collectors in the attic. The caricature is someone sitting on the couch watching infomercials at 2am, seeing a fitness product enthusiastically pushed on TV, and ordering it online. It shows up, gets used a few times, and becomes a clothes hanger. That’s partially why so many in the investment community think skeptically towards Peloton—they assume it’s a fad that will run its course. Obviously, I disagree with that but that is contributing to why the stock is cheap.

To address the “Will I use it” concern, Peloton rolled out its 30 day Home Trial last October. You buy the bike, use it for 30 days in your home, and if you decide it’s not for you, they come pick it up and give you a full refund on the bike and anything you spent on the subscription.

Management said this generated a lot of sales growth while also having lower return rates than expected. More people kept the bike than they thought would. The Home Trial is now a permanent feature.

Company History

Peloton Interactive (“Peloton”) was founded by John Foley in 2012. He and his wife were big fans of boutique spin studios, but there were several drawbacks. If you wanted to a spot in a specific class with a certain instructor, you had to remember to reserve your spot or it would sell out. That might be the only time that works for you that day. You could get a spot in the back with a bad view. These classes also cost $30 or sometimes up to $40 per class each. For a couple, that’s $60-$80 for a single class.

Foley thought there had to be a way to stream this into homes and create great scale economics. He started developing Peloton with a few other co-founders, but were consistently turned down by VCs who didn’t think it would ever work. As he tells the story, VCs were often looking for online platforms, the next Instagram for example, which had recently been acquired by Facebook. These companies could scale massively and grow without much capital.

In contrast, Peloton was a complex business model. Physical fitness product manufacturing would require a big investment in inventory, which ties up working capital and also represents a big risk if the product never catches on. On top of that there’s running the retail spin studio(s) with a wide variety of instructors and real in-person members. That leads to the content production and production crews, the streaming technology, the many software engineers required to maintain and improve the software. Then there’s the physical delivery and logistics network required, the equipment maintenance people, the fleet of nationwide physical showrooms, and the apparel business. While some will laugh at the short-sighted VCs who asked, “Where is the research that shows consumers want to buy a $2,000 bike?”, it is at least understandable that Peloton was a more complex business model and perhaps higher risk than many of the digital platforms that were being funded around them.

To make a long story short, Peloton eventually received funding and has nicely rewarded those investors.

Impact of COVID-19

Peloton came public in September of 2019. Its first two quarters as a public company were strong. Connected Fitness subs grew 103% and 97% year-over-year, respectively. Subscription gross margins expanded from the high 40%s into the high 50%s due to the fixed cost leverage seen when producing the same content for more and more subscribers.

Demand started to accelerate even higher in early March due to COVID-19. Management quickly halted Tread sales because they require technicians entering homes and assembling the Treads. Bikes were still available to order because management switched it to “threshold” delivery where the delivery personnel leave the bike just inside your door and no assembly is required. As I mentioned earlier, order-to-delivery times expanded to at least 10-12 weeks at one point. There simply was no time to prepare for that kind of overwhelming demand that was so unexpected.

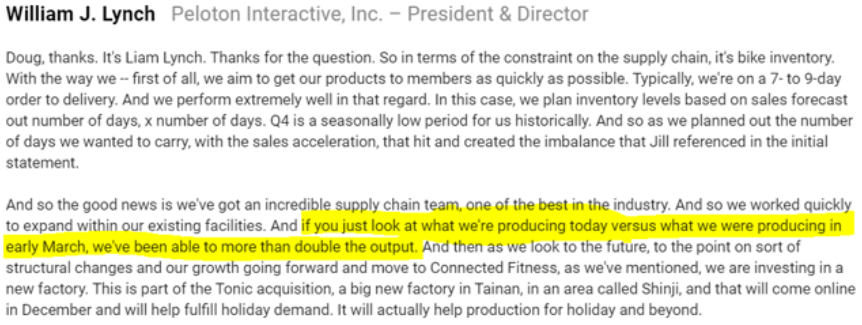

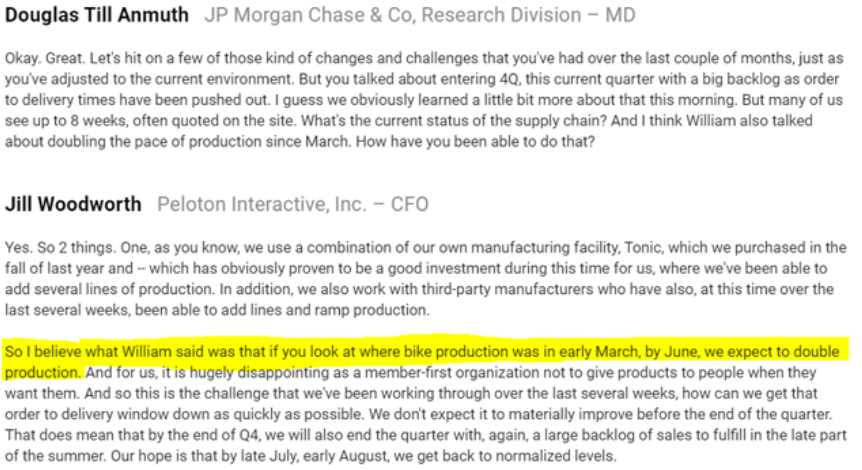

The company added on another manufacturing line at a facility in Taiwan and has generally done everything possible to accelerate production. Interestingly, William Lynch, the COO, said this on the company’s fiscal 3Q call on May 6:

Wow, doubled the production output by early May versus early March. That’s great. But at the J.P. Morgan conference on May 12, there was this exchange between the J.P Morgan analyst and Jill Woodworth, the CFO:

As you can see that’s not exactly what William said. He said it had doubled already and said that on May 6. I don’t know where the miscommunication was, but either way it appears as though they have doubled production now. Big picture, not a big difference.

Anyway, why is that so interesting? Bike backlogs are still 6-8 or 7-9 weeks. They are making twice as many bikes as they were in early March pre-COVID yet they still can’t fulfill demand on time. That is through-the-roof demand.

Management has said they expect to start meeting demand on time in the late summer, and then the new Tonic facility they’ve been investing in should be able to meet holiday demand later this year. I’m wondering whether the new Tonic facility will enable them to roll out the cheaper Tread for the holidays. I think that would be a massive seller.

Sales and Marketing Impact

Obviously, through-the-roof demand is great for business. But that has several favorable second-order effects. The $1,100 they used to spend to acquire one customer is now certain to plummet because a) demand is higher than ever, and b) they don’t have to advertise in established markets. I think it could easily fall something like $300 or $400 to acquire a customer. That’s going to result in accelerated growth and higher profitability much sooner than anyone previously expected.

In fact, Jill Woodworth has strongly suggested that profit margins should see meaningful upside in the years to come, partly as a result of COVID-19. Thanks to COVID, they may never have to return to the heavy brand building and advertising spending levels seen just a few months ago. The larger subscriber base drives more word-of-mouth marketing, and like a snowball rolling down a hill, it spirals along by itself. At the Cowan virtual conference, Jill said fiscal 2020 is going to be the peak year for sales and marketing as a percent of revenue as wel as for G&A as a percent of revenue.

As I mentioned earlier, the huge cutback in advertising (ex-Germany) is going to reduce sales and marketing spending by about half in fiscal 4Q (ending June):

And management’s language elsewhere has suggested that most active media spending going forward will be focused on new product launches and new market launches, not ongoing brand building or everyday advertising. So a reduced S&M as a percent of revenue should continue indefinitely.

As for G&A, fiscal 2020 had a lot of new public company costs, so they should see nice leverage on that line going forward. R&D, the other opex line, is targeted to remain at 5% of revenue, which suggests healthy R&D dollar spending growth, which I fully support. It’s going to take an ongoing R&D commitment to continue to “Wow” members with new software features and new hardware in the years to come.

While Peloton’s stock price has performed well lately, I don’t think it is pricing in the extent of how much their P&L over the next few years is improving versus where it otherwise would have been.

Subscription Cost of Revenue

The most important thing to understand when modeling Peloton is the company’s fixed versus variable cost structure in the subscription business. That’s the key to understanding Peloton’s long-term margin profile.

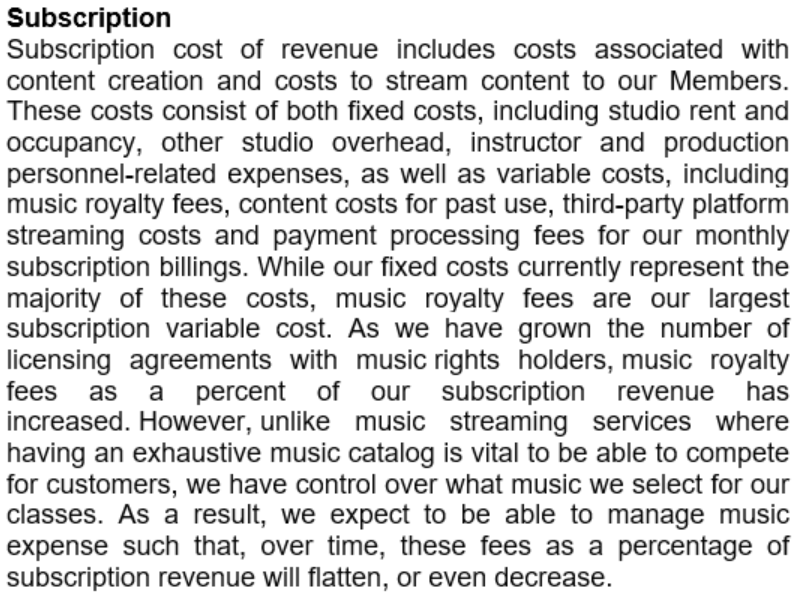

Here is the definition of subscription cost of revenue from the S-1:

You’ll notice it says “our fixed costs represent the majority of these costs…” That was as of September last year. As the company scales, the fixed portion should rapidly shrink as a percent of the total subscription cost of revenue.

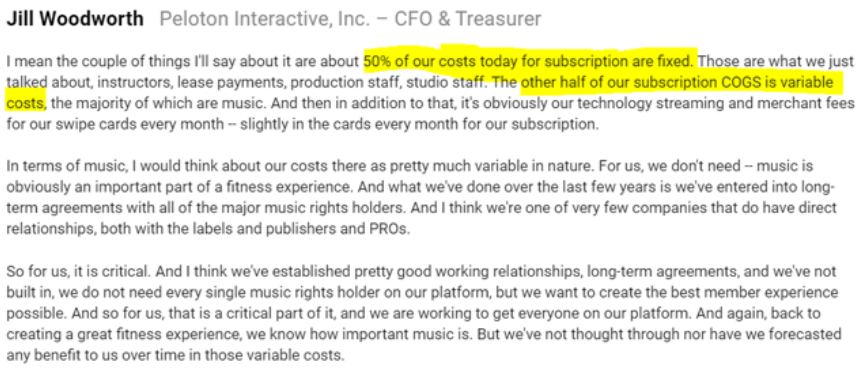

Then at the Barclays conference in December, Jill said this:

Same thing on the fiscal second quarter call in February of this year, when CFO Jill Woodworth made this comment:

All of those fixed costs will be leveraged over time because we only need those two production facilities over the next several years to continue to grow our member base. So we’re going to see a lot of fixed cost leverage for about 50% or so of our cost base today.“

So the fixed portion has gone from “majority” of subscription cost of revenue per the S-1 to “about 50%.”

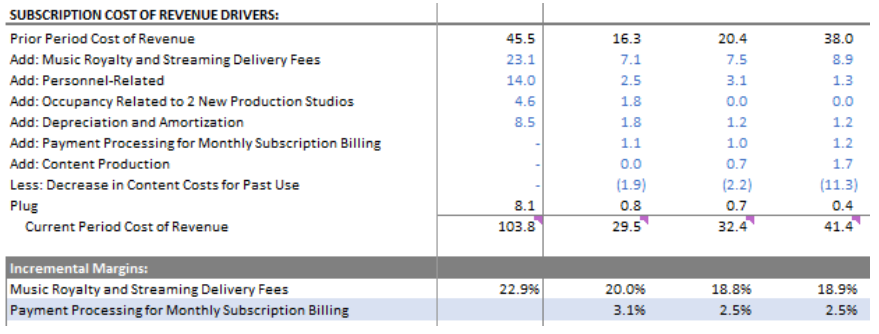

I set up this part in my model using the language from the subscription cost of revenue section in the S-1 and the last three 10-Qs to try to get a stronger grasp of the incremental margins for the variable costs.

You can see music royalty and streaming delivery fees is the single largest variable cost by far—that’s been about 19% of incremental subscription revenue the last two quarters. And payment processing, the other variable expense, is about 2.5% of incremental subscription revenue. If you look up at the definition of subscription cost of revenue I posted above, those are all the variable expenses, except content costs for past use, which I don’t think is going to be relevant going forward. So that implies variable expenses are about 21.5% of incremental subscription revenue going forward.

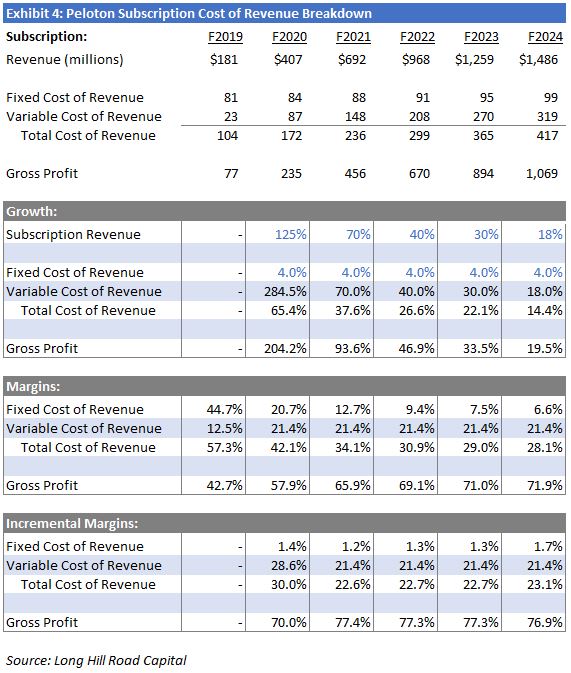

Next, Exhibit 4 shows how I think subscription cost of revenue and gross margin works under the surface.

You can see how in F2019, fixed cost of revenue was the majority of total cost of revenue; then in F2020 it’s about 50%—seemingly consistent with the company’s statements I mentioned earlier.

In this model, I have fixed cost of revenue growing by 4% per year. Fixed doesn’t literally mean fixed; there’s inflation, there may be a few instructors added that’s not going to recur, and things of that nature. I have variable cost of revenue growth linked to subscription revenue growth.

With these assumptions, you can see incremental variable cost of revenue is 21.5%. I basically backed into that by tweaking the $81 million fixed cost of revenue figure in F2019. So I think this is pretty close to accurate.

As the company grows subscription revenue, the fixed portion of cost of revenue doesn’t grow much, the variable portion does, and overall margins see tremendous leverage. Incremental gross profit according to this model is about 77%. I think that’s fair considering management has suggested 70%+ subscription contribution margins long-term.

If I’ve lost you, the point of doing this was to understand how much more profitable the subscription business will become as it grows over time. Rather than 77%, I use a 75% incremental subscription gross margin in my scenario analysis to hopefully air a tiny bit on the conservative side. It’s really helpful for me to do this exercise because it provides some analytical support for management’s 70% contribution margin comments.

Scenario Analysis

Some of the key variables on the revenue side are gross Connected Fitness subscriber adds and average monthly churn.

The subscription price of $39 per month is pretty firm—John Foley the CEO has even called that price point “sacrosanct.” That said, I do assume a 5% price increase in 10 years and another 5% in 20 years. Even a sacrosanct price can’t stay flat for 20 years given inflation.

As for margins, I assume Connected Fitness Product margins decline over time as the mix of lower priced mass market bikes and treads are released and grow within the mix. Management has said this will happen. I assume 75% incremental subscription gross margins, which as I wrote earlier, I think is consistent with management’s comments and in line with what I’ve derived from the disclosures the company provides about the dollar amounts that the variable costs have increased year-over-year.

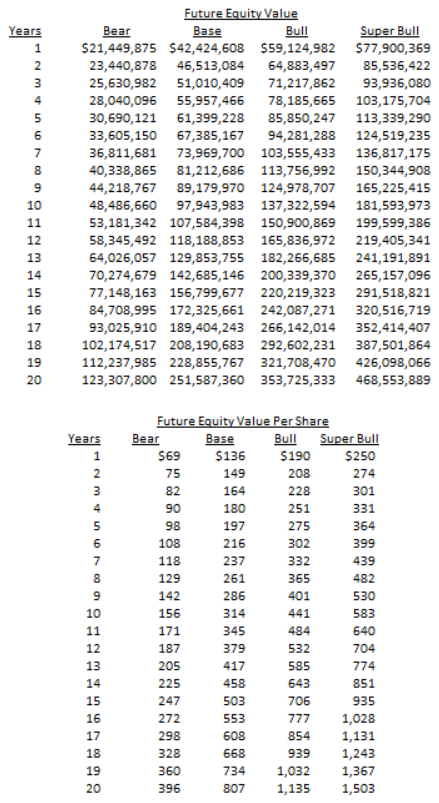

Looking out 20 years, the company has about 9 million Connected Fitness subs in my Bear case, 19 million in my Base case, 26 million in my Bull case, and 34 million in my Super Bull case. I intentionally designed my Bear case to back into an equity value that was roughly in the neighborhood of the current stock price—a reverse DCF.

Not that anyone should hang their hat on this comment, but if you recall, John Foley recently made a remark about 20 million subscribers in “pick a number,” 10 years. Only my Super Bull case beats that growth pace.

I can see Peloton having consolidated gross margins in the 60%s as subscription revenue grows to become the vast majority of revenue. I see them leveraging sales and marketing more and more as they rely more on word-of-mouth marketing and other unpaid channels (more ESPN races between professional athletes?). G&A should see lots of leverage as revenue scales. And I have R&D remaining close to 5% of sales over the long term. But even that assumption seems a little high because it implies the dollar amount of R&D is almost $600 million in 2040 in my Base case. That seems crazy high relative to this year’s $80 or $90 million, but I guess it is possible.

Management hasn’t said much about capital expenditures, but I believe they have completed work on the new New York and London studios. The new manufacturing facility with Tonic remains in the works and should be done later this year. So I think capex can normalize next year. I then assume it grows 3% per year forever. Management has said that these two studios have plenty of capacity and therefore should be able to support content growth for a long time. They will probably open small satellite studios in foreign markets over time as well as retail showrooms.

Here’s my 20-year scenario analysis and the four associated DCFs (click the button to make it full screen; it may take up to 30 seconds to show up):

Peloton-Scenario-Analysis_2020.06.23You may notice I have no revenue or gross profit for the Other segment, which is mostly apparel. It isn’t clear to me that this business will contribute meaningful gross profit over time. It’s one of the questions I plan to ask management about when I hopefully talk to them, but either way it shouldn’t move the needle.

And here is my valuation summary exhibit:

For new readers, my business valuations in the top row are derived from the four DCFs, which are of course a function of the assumptions in my 20-year scenario analysis. Given that the value of a business is the present value of all future cash flows, I like to explicitly lay out several long-term scenarios, discount those cash flows, and figure out what a business could be worth if those scenarios play out.

It’s popular to apply an earnings, cash flow, or revenue multiple to a business that seems like it could be appropriate, but there is a huge margin for error when you do that. I would have no idea what long-term expectations I would be betting on if I did that. For example, there’s no way to know from applying a multiple what you’re assuming for Connected Fitness subscribers in 10 or 20 years, what gross margins could be, how much leverage they’ll get on sales and marketing, G&A, or R&D and those sorts of fundamental questions.

Certainly, there is also a huge margin for error in any long-term scenario analysis. But at least I know what the assumptions are, I can tweak them as time goes on as I learn new information or have new realizations about the business, and I can see where I under or over-estimated things in the past. No one has a crystal ball, but explicitly laying out the assumptions at least gives me a sense of what sort of assumptions could be priced in at varying stock price levels. And that’s really the point of all this—not to pound the table that my Base case should be written in stone, but that my Base case, if it were to play out, would suggest to me that the business is worth something like $37 billion today.

I’m also not here to tell you what to think. You may look at the assumptions in my scenarios and not be comfortable betting on any of it playing out. That’s fine, even great. After all, every scenario could end up wildly wrong. But at least you’ve come to that conclusion by considering and rejecting explicit long-term assumptions rather than by guessing by saying “the multiple looks too expensive.” To me, the difference is like driving on the highway with your eyes open or closed.

Forward Return Tables

For new readers, I use these tables to show what Peloton’s equity value might be in the future given my valuation work. If Peloton is worth $37 billion today, in one year it would be worth 10% more or $42 billion assuming my Base case plays out, and so on. This is very academic because there is zero chance any of my scenarios will play out exactly, but my best guess right now is the future will fall somewhere within these (admittedly wide) ranges.

For example, if my Base case plays out, then I’d expect the stock to be worth something around $314 per share in 10 years. That’s 5.9x from here and a 19.4% annualized return, as you can see in the tables, assuming it trades at that future fair value at that point in time.

Final Thoughts

Investing is all about trying to get a decent understanding of what expectations are priced into a given stock, and trying to pay a price that reflects much more modest expectations than you think are likely to play out. That’s just another way of saying you’re trying to buy a stock at a big discount to what you think it’s worth.

I will say this about Peloton: I’m pretty confident you’re not going to share my confidence in the company’s future unless you own a Peloton bike or tread already, you buy one and become a subscriber, or maybe if you have a relative or close friend who won’t shut up about Peloton. One of those things has to be going on for someone to understand how different and beloved this company is among its subscribers.

Otherwise, you will think, “Ok, but why is Peloton going to grow like this when there are all these competing connected fitness products from Nordictrack, a knock-off bike from Echelon, or another from Bowflex?” “Why can’t anyone just copy what Peloton is doing?”

The answer is those companies are trying to copy Peloton. But Peloton is really the gold standard in product and experience. Existing fitness companies that don’t have a culture of software engineering, an ongoing relationship with the user, a well built out customer service or delivery and logistics team, and or working with world-class instructors from day one…. it’s hard to change your culture on a dime, stand all that up, and be a serious competitor to Peloton.

Peloton has such a larger user base than everyone else, and that drives the community aspect of it and the social engagement. Are you really going to buy the bike that none of your friends have? When your friends who have a Peloton swear by it?

Importantly, that scaled user base and high NPS scores give management the confidence needed to continue investing in R&D. That’s super important. There is very little chance they are going to get cold feet and start to wonder if maybe their R&D dollars won’t have a strong return—but that’s precisely the question its competitors are probably losing sleep over on a regular basis.

I’m not personally familiar with all the competitors as a user, but I’ve read that several of them don’t even have live classes, or the bike feels cheap and wobbles, or the customer service is abysmal. It’s hard for a company like NordicTrack to get into a completely different business like hosting live spin classes with real members and setting up high quality television production, editing, streaming, and the like. Especially when they are coming from so far behind. There’s no wonder that the Official Peloton Facebook group has 304,300 members as of today while the equivalent NordicTrack Facebook group has about 5,500. And the Peloton group has added around 87,000 new members so far this year while NordicTrack has added about 4,500.

In fact, I recently joined the NordicTrack group to read some of the posts. Several people complain about the bike wobbling. Many are surprised and disappointed to learn that there are no live spin classes. It also doesn’t license real music, so users have to play their own music from some separate device. Is NordicTrack really going to make these investments while having a tiny fraction of Peloton’s member base and subscriber revenue?

I’ll stop there for now. I plan to reach out to industry sources and potentially former employees to chat with. I may do my own consumer surveys as well. If so, I’ll share it all with the group. Peloton is heavily shorted so I may write another post about all the short arguments and why I find them unconvincing.

And remember, use my referral code 39VER7 if you buy a Peloton to get a $100 credit off accessories. While the bike was not cheap, my view is there’s nothing more important than health. I like to think I’ve added years to my life relative to the alternative.

Disclosure: Long PTON