- The bear case on Spotify is essentially that it is no Netflix. There is truth to that today, but it should become more Netflix-ish over time. And expectations are low.

- Management naturally sandbagged their long-term profitability targets at their investor day because, I believe, pointing to lofty profit targets would be unhelpful in negotiating royalty concessions from the labels.

- Spotify will continue to diversify away from the major labels and get more into higher margin podcasting, higher margin direct licensing of unsigned artists, and higher margin user data monetization.

- Spotify’s growth runway is massive, streaming music is still in its infancy globally, and it is in all music industry constituents’ interests for Spotify to grow much bigger.

- Competition is a formidable, but Apple Music is the only legitimate paid streaming competitor. AM does well on iOS, but has virtually no presence on Android devices, which have ~75% market share globally.

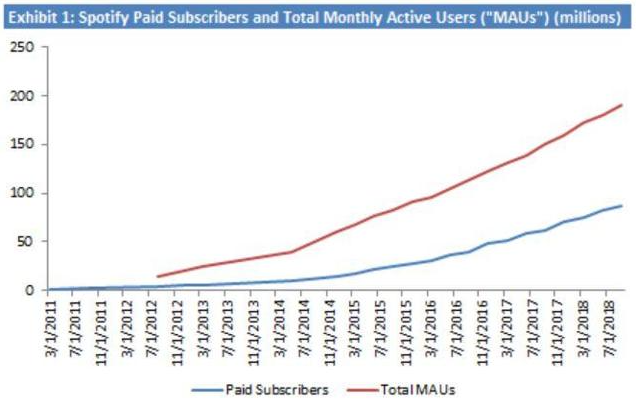

Spotify is the world’s largest music streaming platform with 191 million monthly active users (“MAUs”) and 87 million paid subscribers. The company launched in Sweden in 2008 and has seen blistering user growth since.

Spotify’s Background

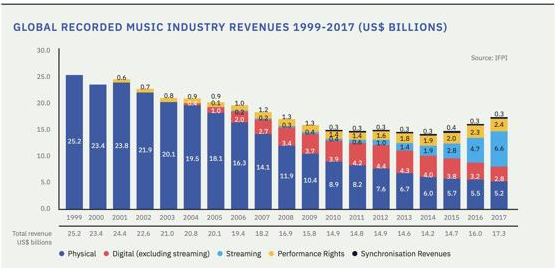

Spotify was founded by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon in 2006 and launched in Sweden in 2008. At the time, the music industry had been decimated by online piracy. File sharing programs like Napster had trained music fans that recorded music is free. Total global recorded music industry revenues had fallen from $25.2 billion in 1999 to just $16.9 billion in 2008—a 33% decline. Touring was beginning to look like the only good way to make money for artists.

By March of 2011, Spotify had 1 million paying subscribers. That figure doubled to 2 million by September of that year, and the growth has been astounding since. Exhibit 1 above shows the growth of the company’s paid subscribers and total monthly active users since then. During the most recent quarter (ending September 30, 2018), Spotify grew paid subscribers by 40% to 87 million and MAUs by 27% to 191 MAUs.

How has this growth been achieved?

First, the service is a great value proposition to consumers. Paying subscribers have access to over 35 million songs, which feels like virtually every song ever created, for a low monthly price ($9.99 in the U.S.). That is an excellent value. When I was a teenager, I had to pay $15 for one CD, which usually had 10 or 12 songs on it. In today’s dollars, that is almost $25. So for 60% of the inflation-adjusted cost of one CD, we now have access to virtually every song ever made, on-demand with unlimited listening, ad-free, and no restrictions. For those users on Spotify’s free ad-supported tier, you have access to essentially the same library of music, although you can’t play specific songs on demand and you have to endure advertisements every 20 minutes or so. But, it’s free and free is a great value proposition.

Second, the service is one of the rare businesses that provides a benefit to the whole industry. Consumers love Spotify because it is a demonstrably better user experience than terrestrial radio. Why? Spotify offers control over which artists, songs, genres, and personalized playlists to listen to at any time. After liking or skipping or removing songs from playlists, the company’s algorithms learn what sort of music you like, and will like, and provide you with playlists of undiscovered music that it thinks you will enjoy. In my personal experience, it is remarkably good at knowing what I will like. On the other hand, terrestrial radio doesn’t know who you are, what you like, or what you want to listen to. It is a linear broadcast, you can’t influence what they play, you can’t skip songs, and you have no control. Whether using the free or paid versions, consumers love Spotify. The paid version particular has a Net Promoter Score of 79, which is considered world class.

As for the artists and labels, streaming has brought the industry back to growth. Artists and labels are making money off recorded music again. The largest music label, Universal Music Group (“UMG”), which is owned by Vivendi SA, grew revenue last quarter by 13.5% in constant currency but the streaming music component of that grew 38.6% in constant currency, and now accounts for 56% of UMG’s revenue. It is also in artists and labels interest to see streaming take share from terrestrial radio because the streaming companies are required to pay royalties to the performers of songs, while the radio companies are not required to do so.

Third, Spotify is a “freemium” model. Most users start out paying nothing for the free ad-supported version. Management has said that 50% of ad-supported users who listen for three years upgrade to premium. The free tier has been a highly effective subscriber acquisition funnel.

Finally, the company has expanded into new territories globally. Spotify started in Sweden and is now available in 65 countries or territories and counting.

Total Addressable Market

Management lays it out this way: there are an estimated 1.3 billion “payment-enabled” smartphones in territories where Spotify is currently active today. 191 million, or about 15% of them, use Spotify on at least a monthly basis. That 1.3 billion should grow to 1.7 billion by 2021. And there are another 1.3 billion in territories where Spotify plans to launch. So the total opportunity is about 3 billion potential users, which is about 16x today’s user base and 34x today’s paid subscriber base. Additionally, the number of smartphones will continue to grow. Said another way, Spotify has far less than 6% of the future addressable market in MAUs and far less than 3% of the future addressable market in paid subscribers. There is clearly a large growth opportunity ahead.

Of course, Spotify is not going to capture the whole market. Certainly, many people will not pay for streaming music, and some may not even listen to the free version. Spotify has competition from Apple Music, Amazon Music, Pandora, Google Play Music, Sirius XM, Soundcloud, Deezer, Tidal, and YouTube, and others, including local competitors.

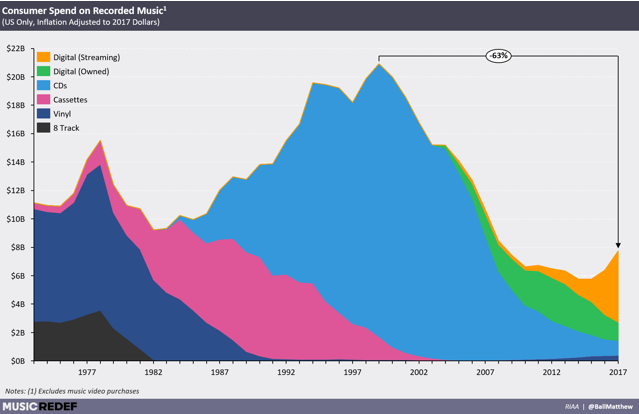

I do think it is instructive to look at total recorded music sales over time by channel. Here is a graphic of consumer spending on recorded music in the U.S. by channel.

As you can see, at the peak of the CD market, U.S. consumer spending on recorded music was around $21 billion or so (in 2017 dollars). As of last year, it was only about $8 billion, a 63% drop. Importantly, the majority of is now made up of streaming and the aggregate number is growing again.

If U.S. consumers were willing to spend $21 billion on CDs, each of which has 10-12 songs, what would they be willing to spend on streaming music? Like I wrote earlier, U.S. consumers were paying $25 for one CD in inflation-adjusted dollars and are now being offered access to almost every song ever created for $9.99 per month. As more people discover streaming music and realize its value proposition, I think streaming has plenty of room to grow in the U.S., notwithstanding the rest of the world. The younger, more technology savvy generation will drive this as 72% of Spotify’s MAUs are under 34 years old and 43% of them are under 24 years old. As more younger people become teenagers and the population mix becomes increasingly comfortable with technologies like streaming music, I think adoption will only increase.

According to The Polaris Nordic Digital Music Survey 2018, 90% of people in the Nordic countries listen to streaming music and 43% pay for it. Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland have 51%, 50%, 46%, and 26% paid streaming penetration rates, respectively. Spotify launched in Sweden first, which probably explains why these countries have such high penetration rates, and suggests more recently launched countries should approach these rates with more time.

If I apply 43% to the U.S.’s 328 million population, that suggests 141 million Americans might pay for streaming music one day. At $9.99 per month in the U.S., that is $16.9 billion of annual revenue. But the population will continue to grow, and there will probably be price increases eventually. If the U.S. population continues to grow at 0.7% per year, and the average monthly rate in the U.S. is $14.99 10 years from now, the U.S. paid streaming market alone would be worth $27.2 billion. Free ad-supported revenue would be additional.

How much of any of this could Spotify have? Well, Spotify is the leading player globally with 87 million paid subscribers, which is about double the number of paid subs that Apple Music has. However, in the U.S., Apple Music just passed Spotify in paid subs. This is because Apple Music tends to be relatively stronger in markets were iOS is relatively stronger, and the iPhone is relatively strong in the U.S. Different sources have different estimates, but it seems like iOS’s market share in the U.S. is probably not too far from 45% of smartphones.

It is a vastly different story globally, however. Android phones have an estimated 76% market share around the world. This, and Spotify’s head start, explains Spotify’s global strength.

I believe the U.S. market will primarily come down to Apple Music and Spotify in the long run, and Spotify should have at least 40% market share. So in 10 years, Spotify could have about $11 billion of paid streaming revenue in the U.S. alone. For perspective, the whole company—paid tier, free tier, and globally—should report about €5.3 billion of revenue for 2018. So there should be a lot of growth to come.

Spotify does objectively seem to have the superior product relative to Apple Music, but Apple’s big advantage is having its app be native on iOS devices. Apple Music has immaterial market share on Android devices, which means Spotify completely dominates when the two are on a level playing field.

Unit Economics

Spotify’s economic model is characterized by relatively high variable costs due to the high royalty payments the company is required to pay music record labels, music publishers, and other rights holders for the right to stream their content. It has been widely reported that Spotify now pays a 52% royalty to labels for their streamed content, down from about 55% prior to mid-2017 and 58% before that. The company also pays songwriters/publishers another 14% or so royalty. The remainder of cost of revenue is distribution costs, credit card and payment processing fees, customer service, certain employee compensation and benefits, cloud computing, streaming, facility, and equipment costs, as well as amounts incurred to produce content. Cost of revenue also includes the cost of the company’s bi-annual discounted trials.

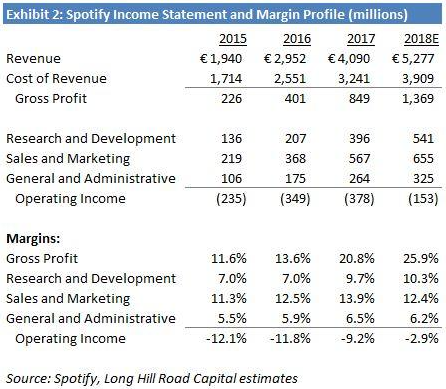

A few things jump out at me from Exhibit 2. First, that’s a 40% annualized revenue growth rate over this period. Second, the company has relatively low gross margins; certainly much lower than those of Netflix, the company to which Spotify is often compared. Third, gross margins, despite being on the low side, have expanded significantly and are funding much greater investments in R&D, sales and marketing, and even G&A. Typically, rapidly growing companies should scale their fixed expenses over time, but we aren’t seeing that across the board with Spotify yet. R&D as a percent of revenues have increased the last two years, sales and marketing as a percent of revenue is still higher than it was in 2015, although it has come down versus 2017. G&A as a percent of sales is also a bit higher than it was a few years ago, but has also come down a bit, despite higher public company costs.

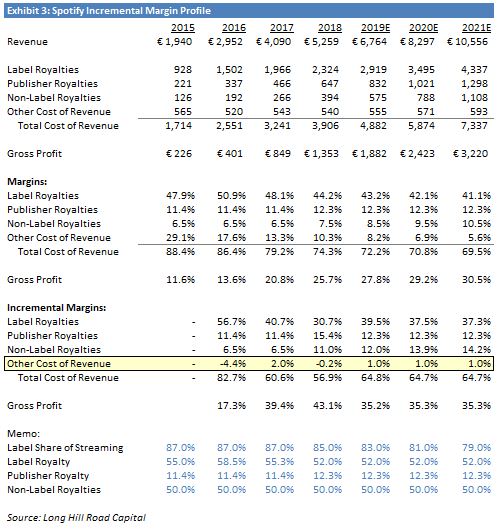

I like to look behind the numbers though, and think about the underlying unit economics, especially on an incremental basis. Exhibit 3 shows my estimated breakdown of the components of cost of revenue.

Basically, the major labels were responsible for 87% of the streamed content on Spotify last year. Between that and a 52% royalty to the labels, I can estimate the “label royalties” component of cost of revenue. I believe publishers have close to a 12% royalty, so I can use that to estimate “publisher royalties.” And Spotify has to pay some royalty to artists who are not represented by the major labels; I assume that royalty is 50% and applies to the remaining 13% stream-share. Finally, I use those estimates plus the overall cost of revenue that is reported to back into “other cost of revenue,” which may have been €540 million last year.

What’s interesting is that “other cost of revenue” as a percent of revenue has been falling like a rock. 29% in 2015, 18% in 2016, 13% in 2017, and 10% last year. The incremental margin on that is highlighted in yellow. Spotify appears to be seeing nice operating leverage on this line item.

Going forward, if the royalty rates stay flat and the labels’ stream share creeps down over time as Spotify diversifies away from them, and they get similar leverage on “other cost of revenue”, then incremental gross margins would be well into the 30s%. That would cause overall gross margin to approach 30% over the next few years.

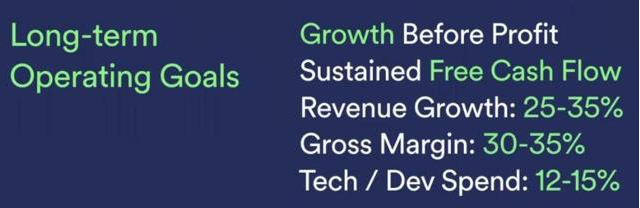

Why is that important? At Spotify’s investor day last year, management disclosed a long-term target of 30%-35% gross margins. To get there, they have said they will need to turn Spotify into a two-sided marketplace where they not only sell their service to users but also sell their user data to artists and labels. This data can provide artists valuable insights, including which cities have their most fans or most engaged fans or which of their songs are more or less popular in which markets. This can help artists decide where to tour, which songs to play on tour, and other insights. But I digress; the point is I don’t think Spotify even has to monetize that data to approach the 30%-35%+ gross margin range. If they keep doing what they’re already doing, it seems like gross margins could hit the low end of their 30%-35% target range in 2021 just based on operating leverage alone, as shown in Exhibit 3.

To the extent management is successful at monetizing its user data by selling it to artists and labels, those benefits would be additional to the gross margins in Exhibit 4. Importantly, an experienced industry professional I spoke with suggested to me that there is no doubt the labels and artists will pay for Spotify’s data and analytics. Management is also expanding aggressively into podcasting, which has higher gross margins than streaming music, “original” content like exclusive sessions or Amy Schumer’s podcast.

Additionally, Spotify is establishing more direct relationships with emerging unsigned artists. Being able to pay unsigned artists directly rather than through the label middleman, Spotify can pay them less than 52% royalties while these artists make up to 5x more than when the labels stand in the way. Here’s the math: Spotify pays 52% in royalties and the labels turn around and pay anywhere from 20% to 50% of their take to the artists. So for every $1 of revenue coming into Spotify from users, the labels get $0.52 and the artists get anywhere from $0.10 to $0.26. When Spotify works with unsigned artists directly, they can pay $0.50 directly to these artists. That improves Spotify’s margins while being an obvious draw for artists since their take increases 2x to 5x. Artists are clearly more incentivized to remain independent today than they used to be, and it is a very favorable trend for Spotify.

Target Financial Model

At Spotify’s investor day in March of last year, CFO Barry McCarthy laid out the following slide illustrating some of the company’s long-term operating goals.

I consider this gross profit and tech/dev spend guidance to be pretty aggressive sandbagging. Consider their incentives. They have to renegotiate their licensing agreements with the labels every so often. When at the negotiating table, would it be in their interests to have publicly disclosed lofty profit targets or not so lofty profit targets? If Spotify had been bragging about its amazing future margins, they could less credibly ask for, or demand, concessions from the labels. But if Spotify appears to have a less robust economic model, it is much more likely to get concessions.

I’ve already outlined why I think gross margin could reasonably get to 30% by 2020 without any big changes. With big improvements in podcasting mix, directly licensed artists mix, and monetizing their data, I think 30%-35% will look quite conservative over time. I see no reason why gross margins can’t get to 40%+.

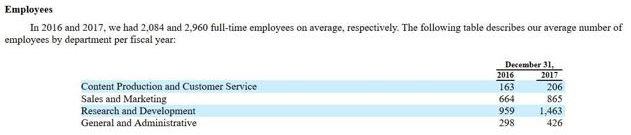

On tech/dev spend of 12%-15%, that is an increase from this year’s ~10% level. Spotify wants to be seen as aggressively investing in the user experience and improving the product. I fully believe they will do that, but they especially want to be seen as doing so for negotiating purposes. Then they can say, “Look labels, we’re investing so much in growing subscribers and revenue, which ultimately gets you paid more. So we’re taking one for the team here, forgoing current profits for more revenue growth. So you’re welcome. Now give us some royalty concessions.” But 12%-15% of revenue becomes a very big number looking into the future. In 20 years, Spotify could have €40 billion of revenue and even 12% of that would be almost €5 billion. There’s no reason under the sun that R&D should be that high when the company is mature. For perspective, Netflix, a much larger company that is also investing aggressively, has spent $1.2 billion on tech/dev over the last 12 months. Additionally, 50% of Spotify’s headcount is R&D employees.

That’s very high, and should come down, not up, over time. I think a more reasonable expectation is for tech/dev to be 12%-13% of revenue for a year or two before operating leverage kicks in and it eventually declines to something like 7% over the long term.

Bear Case

There is a popular narrative around Spotify that goes something like this:

“Spotify has a good product, but it is beholden to the major music labels who supply the vast majority (87%) of its streamed content. As Spotify grows and scales some of its fixed overhead expenses, the major labels can just demand more money since Spotify is entirely dependent on the labels and would disappear without the labels’ content.”

And,

“Spotify will never be the ‘Netflix for music’ because it has a variable cost structure. Spotify’s cost of revenue is about 75% of revenue because its royalty rates are so high. Those expenses grow as revenue grows, so there’s no opportunity for operating leverage. In contrast, Netflix licenses content on a fixed cost basis, meaning no matter how many people view a certain piece of content, Netflix is still paying a flat fee and has huge incremental margins. And Netflix makes original content, which also has fixed cost attributes. That allows Netflix’s model to scale beautifully because it doesn’t have to pay more for content just because more people are watching it. Spotify has to pay more to the labels for every incremental streamed song.”

When Spotify was getting ready to go public, I read these views and nodded my head. It is a good narrative, it sounded like it made sense, and I didn’t know enough about Spotify to question it. As a result, I prioritized other companies in my research. However, the market volatility since October has driven SPOT down by almost 40%, and another professional investor friend of mine suggested I take a close look.

After working on Spotify for a few weeks, the key insight I had is there is truth to these “consensus views,” but that does not mean SPOT can’t be a great investment. As always, it depends what expectations are baked into the stock price and whether I think those expectations are conservative enough to make an investment.

And, this is important, the current status quo can change. 87% of Spotify’s streams may come from the big labels today, but that should decline over time. Spotify is diversifying away from the big labels through podcasting (they are now #2 after Apple), some exclusive content, and direct relationships with unsigned artists. Over time, I fully expect that 87% to fall and for Spotify’s margins to benefit from that, as well as, the operating leverage they should continue to see on the “other cost of revenue” line. Further, the bigger and more influential Spotify gets in terms of being able to break new artists through music discovery, the better terms they should be able to negotiate.

Regarding being beholden to the labels, Spotify certainly relies on the labels for content, but the labels rely on Spotify for a large and growing piece of their revenues and profits. Do the labels really have Spotify over a barrel or is this a more nuanced, symbiotic relationship? How could that relationship change over time as Spotify grows and becomes an even larger part of the label’s revenues and profits? These are all complicated questions and the answers are more complex than the generalizations and sound bites would have you believe.

After reading industry reports and speaking with industry sources, I think Spotify is now large enough and important enough as a revenue source to the labels, that the labels cannot simply dictate terms. The labels certainly cannot pull their content from Spotify. Doing so would cause a very large chunk of their revenues and profits to evaporate and would cause their artists to revolt at their much lower royalty checks. And if one label pulled content, it would just be ceding revenue to the other labels who would now have a greater share of Spotify’s streams. Major label executives have even publicly dismissed that possibility.

The irony is that it is partially because of these consensus views that SPOT can be a great investment because these negative views are priced into the stock. For example, if these things were not true, and Spotify had all fixed cost content deals from a very fragmented supplier base, SPOT would probably be trading at double today’s price or higher.

I will share my Spotify scenario analysis and valuation work in another post shortly.

Disclosure: Long SPOT