Netflix 1Q 2021 Update

- Netflix reported its first quarter results earlier this week.

- Paid net adds will be weaker than expected in this year’s first half before accelerating in the second half due to a stronger content slate.

- Engagement and churn both improved yoy. Netflix’s long-term future remains as bright and secure as ever.

- My Base case implies we could make almost 15x in NFLX from here over the next 20 years. That’s certain to be wrong one way or the other, but I expect strong long-term returns.

Here’s the shareholder letter:

https://s22.q4cdn.com/959853165/files/doc_financials/2021/q1/FINAL-Q1-21-Shareholder-Letter.pdf

Despite the immediate stock price reaction, it was a fine 90 days. The modestly disappointing part of the report is the ~4 million paid net adds, which missed management’s guidance of 6 million, and the second quarter guidance that calls for only adding another million subscribers.

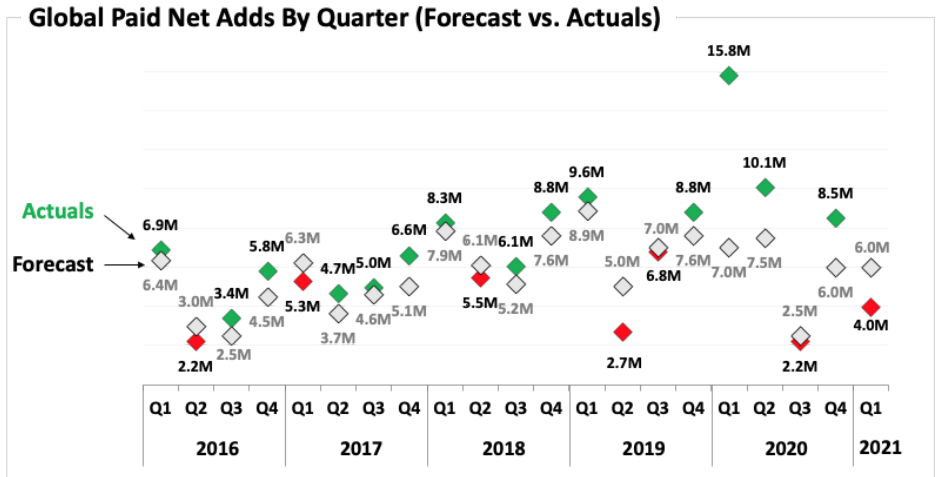

The reasons are two-fold: COVID-19 pulled forward a huge amount of demand last year, and COVID-19 caused production delays that pushed out a lot of content that should have hit the service in the first half of this year into the second half. While both of these were known to management when it gave guidance, it has been a challenge for them to forecast paid net adds during COVID. You can see how big of a challenge that has been by looking at the greater disparity between their forecasts and actuals over the last five quarters compared to pre-COVID periods.

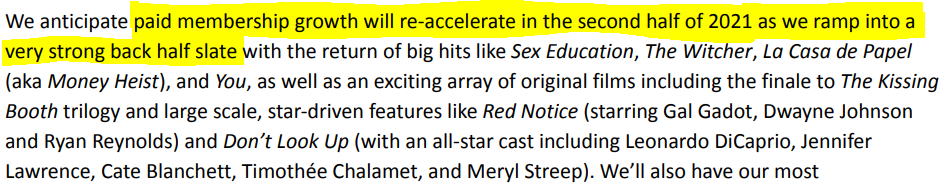

While management does not give full year guidance, it expects the second half content slate to be much more impactful on sub growth than the first half. In addition, year-over-year comparisons get relatively easier in the second half. From the shareholder letter:

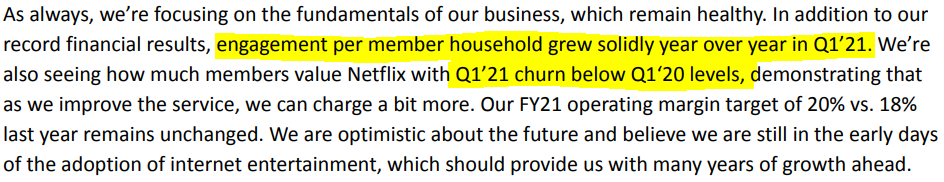

While the first half will be lighter than expected for paid net adds, the far more important underlying facts are that member engagement was up and churn was down in the quarter.

On one hand, that isn’t too surprising because COVID-19 didn’t hit in a big way, at least in the U.S., until March of 2020. So in a mostly pre-COVID quarter, Netflix’s engagement and churn were less favorable than this quarter. Again, not too surprising.

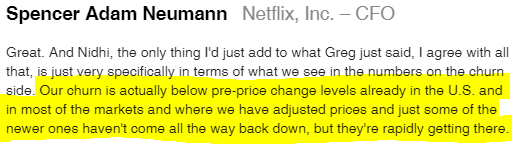

On the other hand, there’s some more SVOD competition this quarter than a year ago. In addition, Netflix just raised prices in the U.S. in December (and elsewhere—Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and perhaps other markets). Despite those prices increases, churn is already below pre-price change levels. On the call, CFO Spencer Neuman said:

Netflix always sees a temporary bump in churn when price increases occur. For churn to have already reverted to pre-price increase levels is impressive. It also highlights how indispensable the service is and the high value proposition.

What would be really impressive is if per member engagement is up year-over-year and churn is down again next quarter when the company is comping against a full blown COVID period. That might be a tall order and too much to expect. We’ll see.

As always, the big picture over the long-term is what matters. There are going to be around 2 billion global households ex-China over the next couple decades. How many will have access to broadband or high-speed internet in, say, 20 years? And how many will enjoy at-home video entertainment? Actually, the better questions are how many of them will NOT have high speed internet and how many will NOT enjoy at-home video entertainment?

Margins

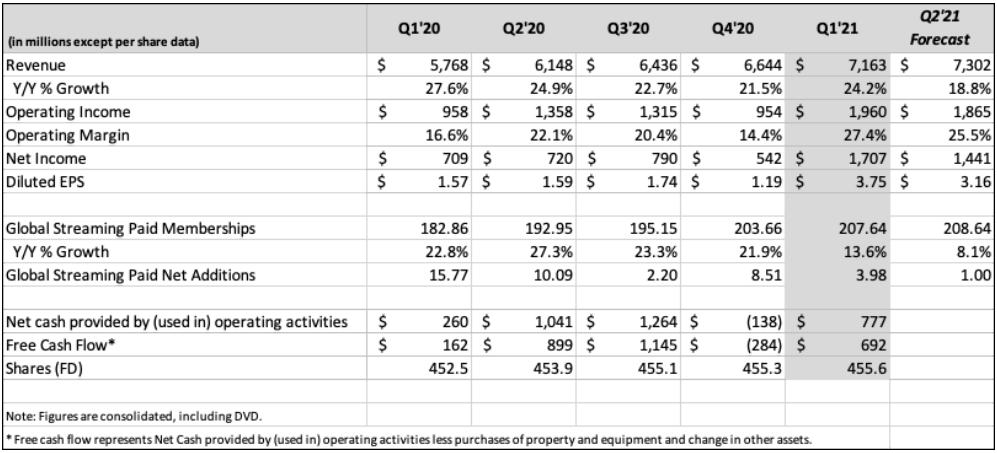

Here’s the summary table from the shareholder letter:

What jumps out at me is the whopping 27.4% operating margin in the quarter. That’s an all-time high. The company was still ramping content production levels late last year, so content amortization only grew 9.5% year-over-year in the first quarter. The lighter content slate translated into lighter growth in paid subs, but also in lighter content amortization, which drove profitability up.

For context, last quarter management said it expected a 20% operating margin for the full 2021 year. Surely, content amortization growth will accelerate later this year, which should drive accelerating subscriber growth and moderating operating margins compared to this quarter’s level. That said, management continuously sandbags its operating margin guidance. It’s hard to keep operating margins from expanding quickly when Netflix’s primary expense is fixed cost content that scales beautifully, including a portion of it that scales globally. I’ll be surprised if the full year operating margin doesn’t handily beat the 20% target for the year.

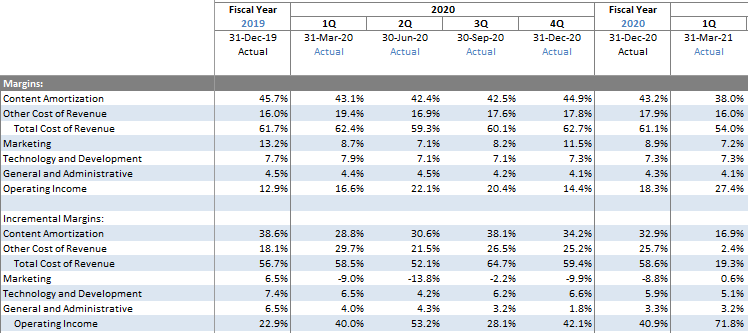

Here’s a screenshot from my model:

As you can see content amortization was just 38.0% of revenue in the quarter, down from around 43.1% in the year-ago quarter. Other cost of revenue scaled down to 16.0% from 19.4%, so total cost of revenue was 54.0% (a gross margin of 46.0%), down from 62.4% a year ago (37.6% gross margin). And marketing, technology and development, and G&A all scaled nicely year-over-year. The incremental operating margin—during a period content amortization is “only” growing 9.5% year-over-year—was an astounding 71.8%.

Obviously, that will moderate for the rest of this year, but I think it does directionally highlight just how profitable the next subscriber is for Netflix. All it takes to begin to see that in the numbers is for content amortization growth to moderate from high-teens growth to ~10%.

Of course, as a long-term shareholder I want to see them keeping their foot firmly on the content amortization pedal for as long as possible. Obviously, that contributes to faster subscriber growth. Because subscriber growth provides the revenue the company can reinvest in more content, driving more sub growth, and continuing that gorgeous flywheel.

It’s also interesting to think about how Netflix’s P&L might look market by market. In certain markets that are more penetrated where subscriber growth is slower, Netflix probably isn’t growing its content amortization as quickly as it is in more nascent markets. I’d love to see how the company’s prior segment reporting—Domestic (U.S.) and International—would look today. Those disclosures not only included subscribers and revenue, but also cost of revenue (which includes content amortization) and marketing by segment. That took us down to contribution profit by segment.

Domestic contribution margin was creeping up over time and got up to about 36% in 2019. I am fairly certain that is higher today. For one thing, domestic sub growth is much slower than international because penetration is higher, which should call for slower content amortization growth domestically. Plus, overall company marketing was actually down in 2020 versus 2019, which is more of a company specific strategy change than a COVID thing. It seems like marketing spending in the slower growing U.S. would be down more than internationally. So I suspect Domestic contribution margin is probably nicely over 40% now, and will continue to climb. And on an incremental year-over-year basis, it was probably 80%+ last quarter.

It is fairly scary how high Netflix’s margins could be in the very long run. For what it’s worth, my Base case has them getting up to the low to mid-50% territory in the long run. For what it’s worth, that assumes Netflix’s content amortization never plateaus. I assume content amortization growth slows over time, but never actually stops growing during this 20 year forecast period. My base case has content amortization getting up to about $43 billion in 2040.

For me, the question is, will they really spend that much annually? I’m not sure management really knows. I think a lot of it will depend on the gap between Netflix and the competition. As long as there’s an opportunity to spend more and then raise prices sufficiently, I think Netflix would continue the playbook. But if management feels like it is getting close to tapping out the average customer’s wallet given the maybe $35 or $40 per month price by then, plus competing services charging more than they do today, then maybe the conclusion will be that growing content spending from $35 billion annually to $40 billion just isn’t going to provide the opportunity to raise prices enough to justify that incremental investment.

I have no idea when that will be or at what level of content spending, but it is interesting to think about. Again, I don’t assume content spending ever plateaus in my scenarios, but if it does, or even slows sooner than I imagine, the incremental profitability should be fairly obscene. Again, just look at the incremental profitability last quarter when content amortization “only” grew 9.5%.

Some investors have been hung up on this idea that to get really profitable Netflix has to pull back on content spending. This level of content spending is unsustainable, they argue. But that reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the business and a lack of appreciation for fixed cost content that scales. If you simply look at the P&L, it is clear that operating margins have been marching higher year after year despite continued rapid content spending growth. If you’re interested in understanding why that is occurring, I wrote some detail about content spending on a per subscriber basis in my last Netflix update.

Content, Content, Content

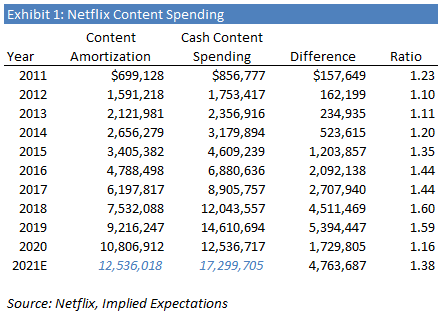

In the shareholder letter, management pointed out the company will spend over $17 billion of cash on content this year. That is up from the $12.5 billion spent last year, which was depressed due to COVID, and up from 2019’s $14.6 billion.

For those who may be less familiar, Netflix’s content amortization expense in the P&L is different than its cash content spending. For licensed content, the company typically pays for it ratably over the term of the license agreement and amortizes it in the P&L on a similar schedule. But with original content, the cash costs are front-end loaded. Netflix pays up front for production well before the finished product hits the service. That spending doesn’t get recognized in the P&L until the content hits the service, which can be two or three years later.

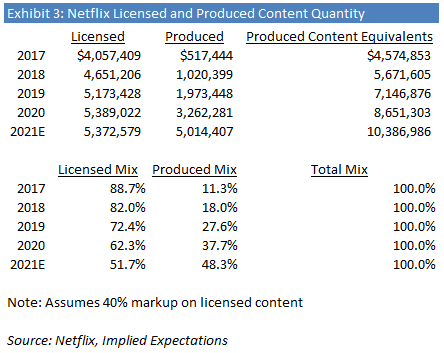

When Netflix was only licensing content many years ago, the P&L and cash expenses were more similar. But as the mix of original content has grown, the mismatch has grown. Here’s a quick breakdown of how this relationship has evolved over the last decade.

Over time, Netflix’s mix of originals has been increasing and will almost certainly continue to increase. For one thing, original productions eliminate a roughly 40% studio markup. In other words, Netflix can produce a piece of original content for about a 29% discount than it would have cost to license the same content from a studio. Netflix also owns the rights in perpetuity so it can do whatever it wants with the content. For example, there has been talk of Netflix potentially licensing some of its older originals to networks, which could help monetize them and act as a form of marketing.

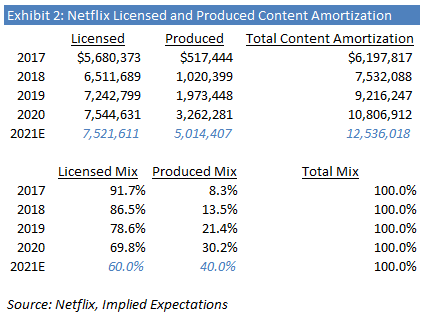

That ratio you see in Exhibit 1 should approach 1.0 over time as produced content gains share of total content. Exhibit 2 shows how that mix, in terms of content amortization, has evolved over the last few years.

I think these figures actually understate the percentage of content on the platform that is produced. Why? Well, the licensed content reflects a studio markup, which is something like 40%. If that’s the case, it means that $1 of produced content gets Netflix more content than $1 of licensed content, all else equal.

In Exhibit 3, I’ve adjusted the licensed content amortization to eliminate an estimated 40% studio markup. This should be a better reflection of the amount of actual content—not just Netflix’s cost—we’re talking about.

As you can see, this analysis suggests almost 40% of content—again, not content spending—expensed last year was produced. And I estimate it should approach 50% this year. While this mix has increased rapidly, there’s still a long way to go. I’m not sure where that mix might settle over the very long term, but Netflix certainly gets a better bang for their buck with produced.

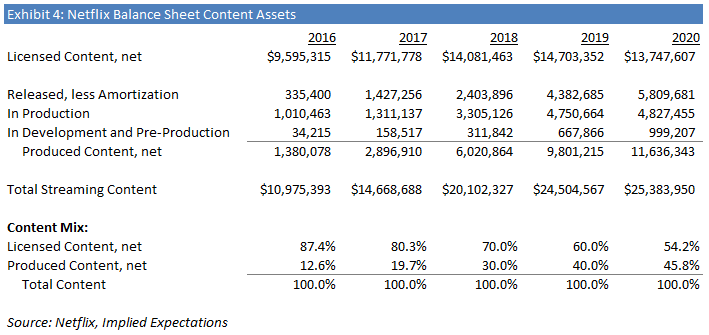

Exhibit 4 shows how the company’s balance sheet content assets break down between licensed and produced.

This is a leading indicator. The produced content on the balance sheet will be amortized in future periods, so you can see where things are going. The point of this is that Netflix’s “per unit” content costs still seem to have a long way to fall as the mix of content becomes majority produced over time. I don’t see this talked about very much, but it should be a tailwind to content costs over time.

Strategy

Netflix is often compared to SVOD competitors like Disney+, HBOMax, Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, and others. What really differentiates Netflix is its strategy of being all things to all people. Netflix wants to make your favorite show, no matter who you are or where you live around the world. You can see this in the diversity of their content just to U.S. audiences—Bridgerton, Kobra Kai, Too Hot to Handle, and The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez (beyond tragic and disturbing, but must watch) are completely different types of content targeted at a range of audiences. The content someone in Europe or South America or India might see could be even more diverse.

I think some investors fail to appreciate there’s a big difference between new SVOD launches and actually competing directly with Netflix. To be a serious substitute for Netflix, a competing SVOD service would have to adopt an “all things to all people” approach. But you can’t do that effectively with a $3 billion or $5 billion budget when Netflix is dropping $17 billion this year. And you can’t drop anything approaching $17 billion unless you have the subscriber revenue to justify it—or you’re willing to take an absolutely massive gamble. As you can see, even tech giants with the resources to do so have decided not to invest that much in content.

Most of Netflix’s competitors seem more like channels to me, focused on their niche. HBO makes a limited amount of “high quality” content. Disney is mostly focused on kids content thus far, although that could evolve. The thing about having less scale and subscriber revenue is these services have less money to reinvest in content. So they focus on their niche. It’s not necessarily their choice. Of course, they would love to have 200 million subscribers paying $11+ per month—if they did they would also have an all things to all people content strategy. But Netflix is the only one with the scale and subscriber revenue to afford to do that. That makes these competitors like channels, while Netflix is internet TV itself. Or they are like channels while Netflix is more like the MVPD, increasingly offering every channel. And as Netflix’s content budget grows from $17 billion this year to maybe $20 billion next year and maybe $23 billion the year after, I think that gap will continue to grow.

I think Disney+ is likely to succeed as an independent SVOD service. They have shown great subscriber growth even excluding Hotstar subs. I think they have an opportunity to raise prices over time, reinvest in SVOD content, and get that Netflix-like flywheel going. But I’m not sure who else has that opportunity. Amazon Prime Video will continue to exist. Maybe Apple has a shot only because of their resources, but it depends how much risk they want to take. Churn is a bigger problem for competing services because they don’t release new content fast enough. And they can’t release new content fast enough with fewer subs and sub revenue, which is in part caused by higher churn. It’s difficult to reach that escape velocity and get that Netflix-like flywheel going.

True Competition

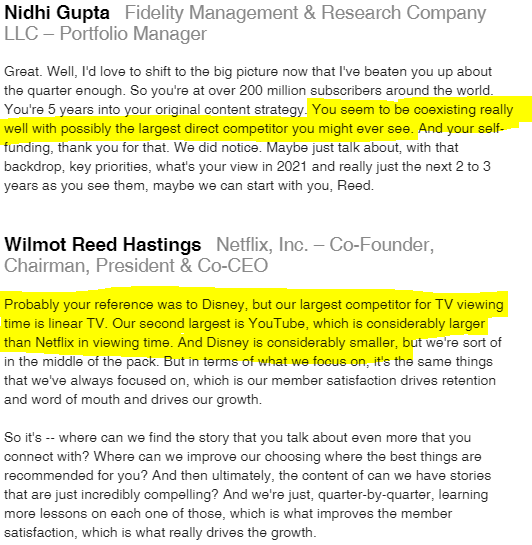

On the call, the analyst implied that Disney+ is the biggest competitor Netflix will ever see. Here’s the question and Reed’s response.

In the past, Reed has also referred to sleep being Netflix’s biggest competitor. I think some people mock these answers but I think they are misunderstood. What really matters to Netflix is engagement because engagement drives retention and pricing power. If you use it a lot, you’re more willing to remain a subscriber and pay more. So it really doesn’t matter what form the competition is, whether it’s linear TV, SVOD, video games, sleep, or otherwise. If Netflix gains share of time spent, it’s a more valuable service to you so churn falls and pricing power increases.

Let’s say linear TV continues to shrink or even goes away entirely one day. In this world, let’s say Netflix’s share of screen time goes from less than 10% today to 25%. Netflix will have tremendous subscriber characteristics and pricing power in this scenario because it is far more important to our lives than it is today. Does it make a difference to Netflix’s engagement, retention, and pricing power who the other 75% of screen time is made up of? If linear TV, other SVOD, YouTube, and gaming make up the other 75%, how much does it matter to Netflix how that mix breaks down? It seems like many investors are still hung up on this idea that Disney+ doing well is bad for Netflix. It’s not. They just aren’t common substitutes. If the scenario is linear TV dies and Disney+ is wildly successful, I’d argue Netflix would also be wildly successful because they would gain a lot of share of screen time. That would lead to engagement, retention, and pricing power.

By the way, I thought Nidhi Gupta from Fidelity, who asked the questions on this call, did a much better job of asking important questions. This may have been the first time a buy side analyst and Netflix investor has asked the questions. There were a lot of “over the long term” type questions, including an interesting one about a “second act.” These questions are so much more interesting and important than some of the shorter term concerns that so many sell-side analysts focus on.

Free Cash Flow and Buybacks

Netflix is now sustainably free cash flow positive. Management says it will be break even for this year before turning positive next year, but I assume this year will be positive given their history of conservatism on this topic. I have always felt this was predictable and only a matter of time given the dynamics of fixed cost content that scales.

The board authorized a $5 billion buyback that should begin to be executed this quarter. I do wonder why $10 to $15 billion of gross debt is the optimal capital structure. It seems arbitrary and not tied to the size and stability of the business and cash flows. For example, when annual free cash flow is $10 or $20 billion per year is $10 to $15 billion of gross debt really going to be the optimal capital structure?

Scenario Analysis

The first thing to point out is my prior expectations for sub growth this year seem too high, given 4 million in this quarter and possibly 1 million next quarter. Sub growth should accelerate in the back half with the more robust content slate, but I’d be somewhat surprised if it were enough to meet my prior range of assumptions. That said, that doesn’t meaningfully change my long run subscriber numbers, which are driven by global households, broadband penetration by segment, and Netflix penetration of broadband households by segment. And the vast majority of value comes from the cash flows attributable to the years far beyond this year.

One thing that I suspect is going to end up conservative is my margin assumptions over the next several years. Netflix’s model results in about 300 bps of operating margin expansion annually. Management recently changed that to 300 bps annually on average, so some years may be more and some less. I think the fixed cost content dynamics and operating leverage make this possible. However, in none of my scenarios do I assume they actually add 300 bps per year, even on average. It’s closer to half that amount. I actually struggle to imagine why that would happen. So that is one area that could end up conservative.

Another area is long-term subscribers. By 2040, there should be about 2 billion global households ex-China. I assume the global broadband or other high-speed internet access penetration rate gets up to the mid 80% range by then. 20 years is a very low time, and governments and technology companies are motivated to expand access. So we could have close to 1.7 billion internet-connected households by then. My base case calls for about 1 billion subs by then, which is a 59.3% of internet-connected households. I think that is achievable and likely conservative, if anything. Consider that pay-TV penetration reached 88% in the U.S. at its peak before cord cutting began. 88% of U.S. households paid a lot of money for an expensive cable package. And as Reed said on the call, pay-TV peaked at 800 million households globally ex-China and that was several years ago, suggesting there are more global households willing to pay for video entertainment today. And there will be even more in 20 years time.

What are all these global internet households going to watch on their screens if not Netflix? They are going to watch something. And Netflix has by far the largest content budget, which is still going to grow significantly, to appeal to every demographic group around the world.

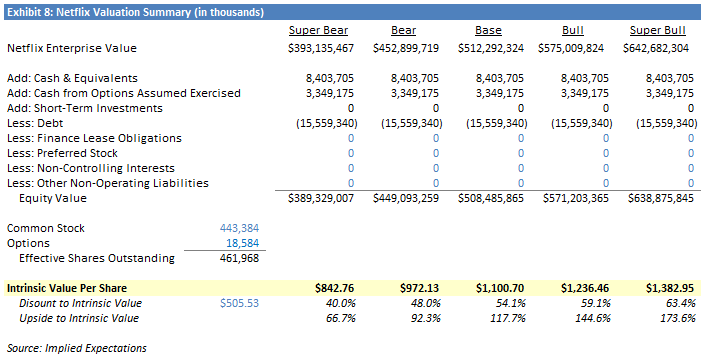

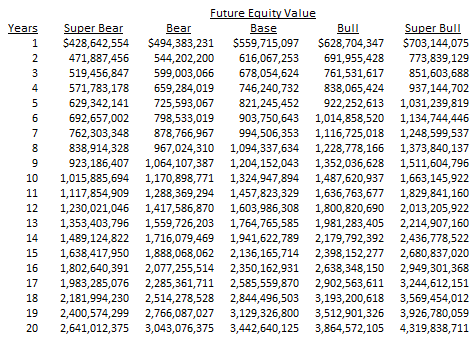

Here is my usual scenario analysis with explicit assumptions and the corresponding DCFs:

I’d encourage you to take a close look at these assumptions, compare them to your own, and shoot me an email (info@impliedexpectations.com) with your thoughts. For example, do you feel strongly that annual content spending will never be $43 billion per year? I’d love to hear why.

And here is the valuation summary that feeds in the business values derived from the DCFs.

None of these scenarios are my forecast, per se. This set of scenarios simply represents a wide range of outcomes that are plausible, in my view. Personally, I think the stock is very cheap. Obviously, these are current valuations. As time goes on, assuming these scenarios played out exactly, these values would grow annually by something approaching the 10% discount rate I’m using. That is in theory, of course, because these scenarios are certain to be wrong to one extent or another. And whether the company’s free cash flows sit on the balance sheet forever or can be intelligently reinvested beyond what I’m assuming will make a difference. But without a crystal ball, that’s the best we can do.

And I think most understand this, but my scenario analysis is built from my perspective and mine alone—that of a Netflix shareholder. Clearly, what I call my Super Bear scenario is going to be more bullish than if the same scenario were built by a Netflix skeptic. It is obviously not a “worst case scenario.” It is a “I’ll be a little surprised if things turn out worse than this” scenario. If you like, you’re welcome to assume I’m also including a “worst case” scenario where Netflix gets disrupted and goes to zero.

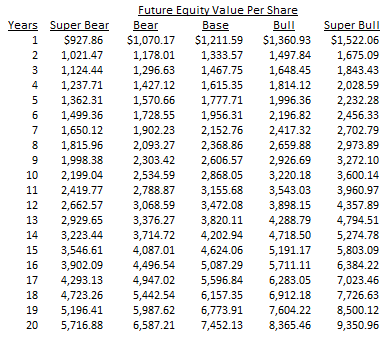

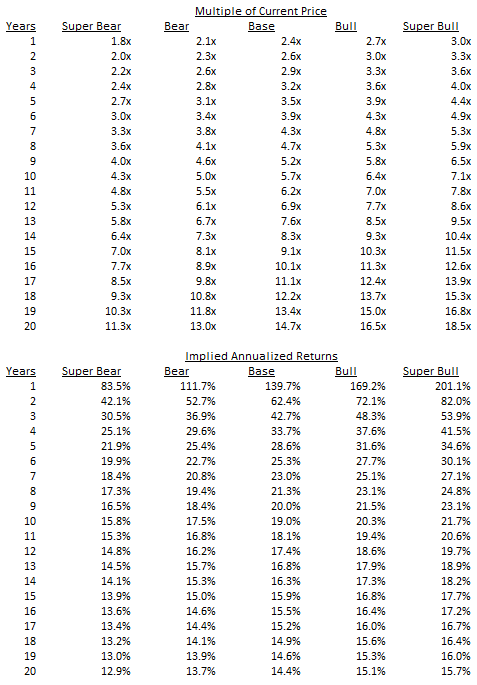

If these scenarios played out exactly and business value compounds at 10%, here is how these values would compound.

Assuming the stock trades at what I deem to be its future fair value at these various points in time, here is what those forward returns might look like.

For example, if my Base case plays out exactly and the stock trades at its future fair value, I would expect something like a 5.7x over 10 years and a 14.7x over 20 years. Obviously, the future is uncertain and each of these scenarios is certain to be wrong. But I’d rather make explicit forecasts and do several different scenarios than guess what multiple of today’s revenue/earnings/cash flow implies a billion subs in 20 years, a certain ARPU, a certain content spending, certain operating leverage assumptions, and the like.

More importantly than getting the future exactly right, I consider Netflix’s long-term prosperity to be as close to inevitable as it gets. The global subscriber runway is super long. The content reinvestment/pricing power playbook is super long. The scale, subscriber revenue, and content budget dwarfs the competition. The benefits of fixed cost content that scales are enormous. What is going to stop Netflix from dominating global SVOD in the long run? And the real beauty of this that I think this view is still considered controversial.

Maybe we’re all watching video content on smart glasses instead of TVs and tablets one day. I think that would be ok. Netflix would be on those smart glasses if the manufacturer wants them to be popular.

Maybe gaming or AR/VR gains share of our screen time. Perhaps, but Netflix is sub-10% of screen time today. Linear TV’s long demise is a secular trend. Gaming, AR/VR, and Netflix can all gain share of screen time thanks to the death of linear TV.

Could all the non-Netflix and Disney+ competitors consolidate into one SVOD player? I doubt they could come to an agreement where they are all happy with the economics. I think it’s more likely that one or more of them would abandon SVOD and license content to Netflix. That is big, easy money. Far easier than competing with Netflix and struggling with churn.

Disclosure: Long NFLX